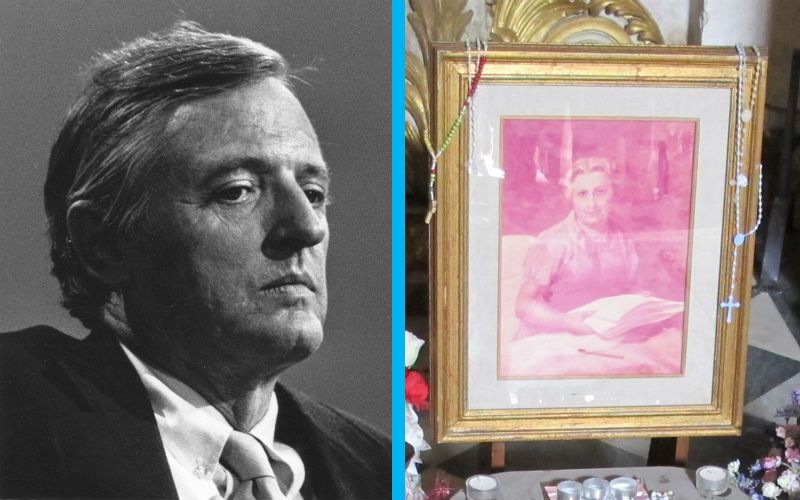

The late William F. Buckley Jr. is usually recognized for his political work. Considered the godfather of the American conservative movement he founded the nation’s most eminent conservative political magazine National Review and, for decades, hosted the television show Firing Line, discussing sociopolitical matters with guests as diverse as Jack Kerouac and Noam Chomsky. Charlie Rose always considered Buckley a personal role model to emulate as a talk show host.

What less people may know about William Buckley is that, in addition to his political and media endeavors, he also led a fascinating spiritual life as a devout Roman Catholic.

[See also: The Miracle that Led “Obi-Wan Kenobi” to Convert to Catholicism]

[See also: The Little-Known Story of John Wayne’s Deathbed Conversion to Catholicism]

His spiritual convictions are what first led a young William Buckley to gain notoriety. As a Yale graduate, himself a Bonesman at the university, Buckley published the polemical and influential book “God and Man at Yale,” criticizing how the Ivy League school he had spent his undergraduate years at had abandoned its Protestant Christian roots with a promotion of secular (and, at times, downright atheistic) values.

As a mature man Buckley also exuded an interesting faith. He was a traditional Catholic who attended the Latin Mass, even after Vatican II reforms—many of which Buckley disagreed with. His son, the novelist Christopher Buckley, explained: “Pup was a defiantly pre-Vatican II Catholic.” To the point that he had a priest say “a private Latin mass for him” every Sunday. Yet, at the same time, William Buckley held a personal devotion to the works of the Italian mystic Maria Valtorta, a significant but controversial figure within the Church.

In his spiritual memoir, Nearer, My God, William Buckley wrote of how he first encountered the revelations of Valtorta. “My nephew Fr. Michael Bozell thought to send me a few years ago some pages from Maria Valtorta, Italian writer and mystic (1897-1961). She wrote a huge five-volume book called The Poem of the Man God, and one part of the fifth volume was her fancied vision of the Crucifixion.”

Maria Valtorta was a twentieth century mystic who, throughout the 1940s and ’50s, reported experiencing visions of Jesus Christ who, according to Valtorta, showed her His life in first-century Palestine which she recorded in her voluminous book The Poem of the Man God. The Crucifixion details of Christ’s Passion were so powerful in Valtorta’s writings and revelations that William Buckley decided to reproduce them in his own spiritual memoir, dedicating 18 pages of his book Nearer, My God, to Valtorta’s visions of Christ’s sacrifice and suffering on the Cross.

Buckley would poignantly write in his spiritual autobiography why it was important for him to reproduce Valtorta’s work in his own book: “And then, too, certain things catch my eye. The painful, detailed ‘vision’ of the Crucifixion by Maria Valtorta (chapter 8) did that when I first read it—so that I proceed simply to pass it along to you, justified only by the conviction that some of you will react as I did.”

Buckley was deeply moved by Valtorta’s descriptions of Christ’s Passion, yet he understood very well that visionary experience is a touchy issue within the Church and, therefore, dealt with it delicately.

“My friend and theological consultant Fr. Kevin Fitzpatrick, who is also a doctor of theology, was a little alarmed with at the prospect of my using Valtorta,” Buckley wrote. “Not so much because her work was, for a while, on the Index of prohibited reading—that kind of thing happens, and there is often life after death.” No, Fr. Kevin’s concerned stemmed from a different matter.

Father Kevin wrote to Buckley: “My main problem is the use of private revelations not approved by the Church. This is not a legalistic concern, but a concern based on some experience of people who, to be blunt, are not satisfied with Revelation which ended with the death of the last Apostle.”

Interestingly, despite his cautious approach, once Fr. Kevin, the doctor of theology, began to read Valtorta’s works to further advise Buckley, what he found – in Valtorta’s revelations – surprised the knowledgeable priest greatly.

“In fact, Valtorta seems to have solved the Synoptic problem that’s been plaguing scholars for centuries, viz., the contradictions between Matthew, Mark, and Luke,” Fr. Kevin wrote Buckley. Her revelations, instead of replacing the Gospels – what Fr. Kevin feared – filled in the gaps that the Gospels possessed which, as Fr. Kevin noted, had confused scholars for centuries. Thus, Valtorta’s revelations helped reconcile for the priest seeming contradictions that exist in the Synoptic Gospels of the New Testament.

While Buckley admired Valtorta’s powerful depictions of the Crucifixion, he may not have known how profound the source of her knowledge was in producing those depictions. For example, Buckley wrote: “The account by Valtorta, or at least that much of it that deals specifically with the suffering endured, would be painful reading describing any death by crucifixion. Valtorta is excruciatingly absorbed by physical detail. Either she was once a medical student or else she studied anatomy, bone by bone.”

The truth is that Valtorta did neither – medical school or studying anatomy. She had a very simple education. Yet, the profundity of her descriptions, which Buckley noticed, is not something that was lost on other observers as well. Dr. Nicholas Pende, an endocrinologist who (like Buckley) displayed immense surprise at the sophistication and accuracy with which Valtorta described Jesus’ spasms during the Crucifixion visions, commented on her descriptions as constituting “a phenomenon which only a few informed physicians would know how to explain, and she does it in an authentic medical style.”

Likewise, Fr. Corrado M. Berti, a friend of Valtorta’s family and a former professor at the Pontifical “Marianum” Theological Faculty in Rome, explained: “I can certify that Valtorta did not, by her own industry, possess all that vast, profound, clear, and varied learning which is evident in her writings.”

What Valtorta reported experiencing, in addition to her visions and revelations, was the mystical grace of supernatural illumination during her experiences – the ability to adequately describe what she was witnessing through a heavenly knowledge that illuminated her mind (during her ecstasies) and transcended her rational human faculties. Buckley, very reasonably, assumed that she must’ve had a background in medical studies due to the sophistication of her descriptions. What he didn’t consider is quite how powerful her spiritual experiences were in producing that knowledge.

Yet, there is no question that Buckley was very open minded toward Valtorta’s work. He admitted, after all, that part of the ecclesial controversy surrounding Valtorta stemmed from the fact that, at one point, her writings were placed on the Church’s (now-abolished) Index of Forbidden Books. However, Buckley was astute enough to recognize that “that kind of thing happens, and there is often life after death.” He was quite correct with this insightful observation.

It deserves attention, after all, that before being abolished, the Index forbade the works of Christian writers and mystics as renowned as Dante, John Milton, and Mary Faustina Kowalska, the latter a Polish nun who reported experiencing mystical visions of Christ in the 1930s (also resulting in written dictations) and who, in 2000, was canonized a saint by Pope John Paul II. Saint Faustina’s revealed writings of theology – the Divine Mercy writings – are recognized today as part of the Church’s liturgical life, having been responsible for institutionalizing both a holy feast day within Roman Catholicism (Divine Mercy Sunday) and a popular prayer devotion to Christ (the Chaplet of Divine Mercy).

Incidentally, as with Maria Valtora, Saint Faustina’s writings were initially placed under the Index by Pope John XXIII. There is life after death, as Buckley observed. Much of Valtorta’s work has already seen this new life. Her writings have already received the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur of a few Catholic bishops, including Bishop Roman Danylak, attesting to the orthodoxy of morals and doctrine within her revelations. Bishop Danylak, additionally provided an interesting explanation as to why works like Saint Faustina’s and Maria Valtorta’s were placed on the Index in the first place. “Theologians and bishops have problems with supernatural phenomena,” he pointed out, recognizing the taboo-nature of the subject in many ecclesial circles.

While this may be the case, the popular portrayal of Valtorta’s work, as being perceived negatively in the Church, is not fully accurate either. Pope Pius XII was a great supporter of Valtorta’s writings, explaining: “Publish this work as it is. There is no need to give an opinion on its origin, whether it be extraordinary or not; whoever reads it will understand.”

Other eminent Catholic leaders and intellectuals have been influential supporters of Valtorta’s revelations after studying her writings, in addition to the former Pope. They include the Jesuit cardinal Augustine Bea, himself an ecumenical star at Vatican II, to Msgr. Hugo Lattanzi, a former dean of the Faculty of Theology at the Pontifical Lateran University, to Fr. Gabriel M. Roschini, the renowned Church Mariologist and philosopher, as well as Fr. Gabriele Allegra, famous for translating the entire Bible into Chinese. Fr. Allegra, who was the first Scriptural scholar to be beatified by Pope John Paul II in 2002 and is currently awaiting canonization, once wrote: “I hold that the work of Valtorta demands a supernatural origin.”

To this list of esteemed Catholics, deeply moved and supportive of Maria Valtorta’s writings and mystical experiences, add another influential Catholic: one of the most significant voices on American political discourse in the twentieth century – William F. Buckley, Jr.

[See also: This Agnostic Scientist Converted After Witnessing a Miracle at Lourdes]

[See also: The Amazing Deathbed Conversion of Oscar Wilde]