Located in Occitania, France, Bonneval Abbey was founded in 1147.

From the beginning, the community was home to a Cistercian monastery, which was later expelled during the French Revolution.

Since 1875, about 20 Trappistine nuns have resided there. And since 1878, these nuns have managed a chocolate factory between their daily services.

Below is the fascinating history behind Bonneval Abbey and its chocolate factory!

Once upon a time, Bonneval Abbey

The history of Bonneval begins in 1143.

Bishop of Cahors, Guillaume de Calmont d’Olt, owned a family castle overlooking Espalion, France.

He then brought seven Cistercian monks from Mazan en Vivarais Abbey, with their prior Adhemar, the “must” of monasticism at the time!

Soon, vocations flowed in and the community grew richer. The monks eventually moved to a more peaceful place at the bottom of a “bona val” (which means “good valley” in english).

And off they went to build the Abbey of Bonneval!

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the monastery reached its peak, both in terms of the number of monks and in terms of goods and possessions.

Unfortunately, the Abbey of Bonneval suffered from the conflicts of its time.

In particular, they faced the Hundred Years’ War and the conflicts with the English in the 14th century. They then faced the European Wars of Religion in the 16th century, and the uprisings in the Kingdom of France in the early 17th century.

Between all the conflict, this period weakened the community in every way. It even caused the brothers and postulants to flee, and affected the application of the monastic rules.

Chaos at Bonneval Abbey

The Revolution further darkened the picture.

Weakened and ruined, the monks could no longer help the poor. Yet the State tolerated the abbey because of this activity. The monks were forced to stop their daily distribution of bread at the door of the monastery, which provoked riots.

Everything changed on Maundy Thursday 1791. According to the archives of Espalion, “a crowd of beggars” forced the abbey to call in the National Guard.

During this event, the brothers and about 50 peasants took refuge in one of the abbey dungeons to resist the furious crowd. The National Guard restored order and expelled the 13 remaining monks.

Only Brother Jean-Jacques Seconds refused to sign the Civil Constitution (which would have saved him from arrest), and was thus deported.

Subsequently, Bonneval Abbey was divided into lots and sold. It gradually transformed into a stone quarry. It was the end of more than six centuries of history.

A sad fate.

The return of Bonneval Abbey and the arrival of its chocolate factory

In 1850, a local priest first suggested that Trappist monks settle there. The latter refused because the place was considered too wild and unsuitable for agriculture.

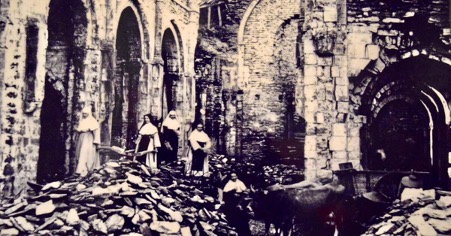

Finally, in 1875, courageous Trappist nuns from Maubec, France accepted the Bishop of Rodez’ invitation to live there. Renovations began in September of that year.

Upon their arrival, Bonneval Abbey was in ruins, the church open to the sky, and the cloister no longer existent. Thus, they used the farm as a temporary monastery.

The nuns were cramped, of course, but at least they were not cold. Fortunately, they depended on the help of Dom Emmanuel, a monk from the Abbey of Aiguebelle.

Work began on July 19, 1877, after the blessing the first stone. The original plan was preserved, as well as the 6.5-foot-thick walls still standing.

Thank you, Dom Emmanuel!

Thanks to the energetic Dom Emmanuel, the sisters began working in monastic crafts. Under his guidance, they developed a small chocolate factory in Bonneval, ensuring their financial autonomy.

Indeed, the sloping soils of the area prevented good land cultivation. Relying on agriculture, a speciality of the Trappist order, was impossible.

The Abbey of Bonneval’s chocolate factory took off quickly, powered by a hydraulic engine drawing its force from the river current.

Subsequently, the sisters won numerous regional competitions.

In 1884, the jury of the regional competition in Rodez awarded them the vermeil medal.

In 1895, their chocolate received the Bronze medal, the highest award given to similar products, at an exhibition in Bordeaux.

In 1927, a master chocolate maker trained the nuns, giving them his secrets to make everyone melt!

Bonneval Abbey today

Today, 21 sisters live at Bonneval Abbey.

They are Trappistines (Cistercians of the strict observance), and thus follow the rule of Saint Benedict “ora et labora” (pray and work).

The first of the seven daily services is at 4:30 a.m. In the meantime, the sisters work hard drying the cocoa, mixing it to obtain each recipe, putting it in moulds, packing the chocolate, etc.

Without forgetting, of course, the smooth running of the guesthouse and the abbey: cleaning, washing up, cooking, etc. They really don’t have time to be bored!

Click here to learn more about Bonneval Abbey and their chocolates.

Follow ChurchPOP:

Telegram Channel

GETTR

Gab

Parler

Signal Group

WhatsApp Group 1

WhatsApp Group 2

ChurchPOP Facebook Group

[See also: How a Few Trappist Monks Came to Brew the World’s Most Exclusive Beer]

[See also: Music, Prayer, & Beer at the Birthplace of St. Benedict: A Documentary]