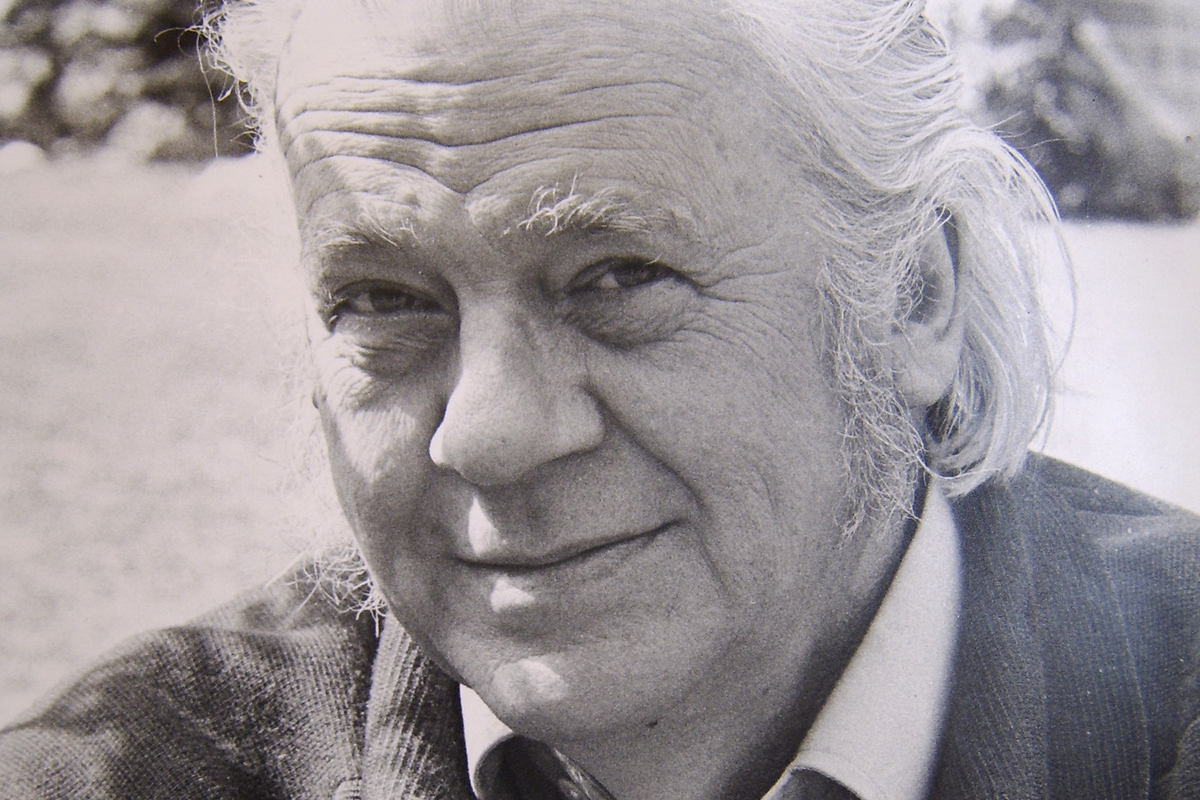

Few realized when Small is Beautiful was published that E.F. Schumacher’s economic theories were underpinned by solid religious and philosophical foundations, the fruits of a lifetime of searching. In 1971, two years before the book’s publication, Schumacher had become a Roman Catholic, the final destination of his philosophical journey.

“It’s all very well to live simply and grow things and practice crafts… but what about the hundreds of thousands who can’t hope to be self-sufficient in property and craft?” This summarizes the complaint by modern critics against “Distributism”—the economic philosophy inspired by Catholic social teaching and developed, early last century, by Catholic thinkers such as G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc. According to Distributism, property should be spread widely, so that people can earn a living without having to rely on the state (socialism) or a small number of individuals (capitalism). According to the pessimistic view of critics, small-scale economies are fine in principle, but are no longer practical.

Such questions were central to the philosophical grappling of Dr. E.F Schumacher, who came to the conclusion that pessimism was self-fulfillingly prophetic. If one believes the worst one will probably get the worst. Negation begets negation. The antidote to such despair, Dr. E.F. Schumacher believed, was hope. It was in this spirit that he wrote Small is Beautiful in 1973, a book which, for a time at least, made Distributism the most fashionable economic and political creed in the world. Schumacher’s trained economic mind had resolved many of Distributism’s alleged problems so that its principles became applicable even to ‘the hundreds of thousands who can’t hope to be self-sufficient in property or craft.’ Schumacher had succeeded where Hilaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton had failed.

Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful, subtitled ‘a study of economics as if people mattered’, was published in 1973 to immediate acclaim and became an international best-seller. At the time of its publication Schumacher was already well known as an economist, journalist and entrepreneur. He was Economic Adviser to the National Coal Board from 1950 to 1970, and was also the originator of the concept of Intermediate Technology for developing countries. In 1967 he became a trustee of the Scott Bader Commonwealth, a producers’ co-operative established in 1959 when the company’s owner, Ernest Bader, transferred ownership to his workforce. Bader, a Quaker, believed that establishing co-operative ownership was an expression of Christian social principles in practice. To the surprise of many sceptics, the Scott Bader Commonwealth prospered, becoming a pathfinder in polymer technology and a model of good labour relations at a time of considerable labour unrest throughout the rest of industry. Schumacher also served as President of the Soil Association, Britain’s largest organic farming organization.

Schumacher became famous throughout the world, idolized as a guru both by the Californian counter-culture and by a rising generation of eco-warriors.

Born in Bonn on 16 August 1911, Schumacher first came to England in October 1930 as a Rhodes Scholar to study economics at New College, Oxford, where he stayed until September 1932. At the age of twenty-two he went to New York to teach economics at Columbia University. Finding theory without practical experience unsatisfying, he returned to Germany and tried his hand at business, farming and journalism. In 1937, utterly appalled with life in Hitler’s Third Reich, he made his final move to England. During the way he returned to the academic life at Oxford and devised a plan for economic reconstruction which influenced John Maynard Keynes in the latter’s leading part in the formulation of the Bretton Woods agreement. After the war Schumacher became Economic Adviser to the British Control Commission in Germany from 1946 to 1950, before becoming Economic Adviser to the National Coal Board, a post he held for the next twenty years.

It was clear that Schumacher’s credentials as an economist were beyond question, but few realized when Small is Beautiful was published that his economic theories were underpinned by solid religious and philosophical foundations, the fruits of a lifetime of searching. In 1971, two years before the publication of Small is Beautiful, Schumacher had become a Roman Catholic, the final destination of his philosophical journey.

The journey began shortly after the war with a growing disillusionment with Marxist economic theory. ‘During the war he was definitely Marxist,’ says his daughter and biographer, Barbara Wood. Then, in the early fifties he visited Burma which ‘was really important in beginning the real changes in his economic thinking’. ‘I came to Burma a thirsty wanderer and there I found living water,’ he wrote. Specifically, his encounter with the Buddhist approach to economic life made him realize that Western economic attitudes were derived from strictly subjective criteria based upon philosophically materialist assumptions. For the first time he began to see beyond established economic theories and to look for viable alternatives. As an economist he developed a meta-economic approach much as Christopher Dawson, as an historian, had developed a meta-historical approach. This fundamental change in outlook was discussed in Small is Beautiful. Modern economists, Schumacher wrote, ‘normally suffer from a kind of metaphysical blindness, assuming that theirs is a science of absolute and invariable truths, without any presuppositions.’ This was not the case: ‘economics is a “derived” science which accepts instructions from what I call meta-economics. As the instructions are changed, so changes the contents of economics.’

To illustrate the point, in a chapter entitled ‘Buddhist Economics’ Schumacher explored the ways in which economic laws and definitions of concepts such as ‘economic’ and ‘uneconomic’ change ‘when the meta-economic basis of western materialism is abandoned and the teaching of Buddhism is put in its place’. He stipulated that the choice of Buddhism ‘is purely incidental; the teachings of Christianity, Islam, or Judaism could have been used just as well as those of any other of the great Eastern traditions’.

Taking the concept of ‘labour’ or work as an example, he compared the attitude of Western economists to their Buddhist counterparts. Economists in the ‘west’ considered labour ‘as little more than a necessary evil’:

From the point of view of the employer, it is in any case simply an item of cost, to be reduced to a minimum if it cannot be eliminated altogether, say, by automation. From the point of view of the workman, it is a ‘disutility’; to work is to make a sacrifice of one’s leisure and comfort, and wages are a kind of compensation for the sacrifice.

‘From a Buddhist point of view,’ Schumacher explained, ‘this is standing the truth on its head by considering goods as more important than people and consumption as more important than creative activity. It means shifting the emphasis from the worker to the product of work, that is, from the human to the sub-human, a surrender to the forces of evil.’

The Buddhist view, on the other hand, ‘takes the function of work to be at least threefold’: ‘to give a man a chance to utilise and develop his faculties; to enable him to overcome his egocentredness by joining with other people in a common task; and to bring forth the goods and services needed for a becoming existence.’

From the Buddhist standpoint, Schumacher continued, to organise work in such a manner that it becomes meaningless, boring, stultifying, or nerve-racking for the worker would be little short of criminal; it would indicate a greater concern with goods than with people, an evil lack of compassion and a soul-destroying degree of attachment to the most primitive side of this worldly existence.

For Schumacher there were three main culprits: Freud, Marx and Einstein.

In England, this view had been advocated already by Chesterton, Belloc, Gill and the other distributists, and also by Dorothy L. Sayers. Yet Schumacher appeared to be unaware of their writings at the time he visited Burma in the early fifties. His introduction to the religious basis of economics was, therefore, a Buddhist not a Christian revelation. Most importantly, however, he had discovered that economics was a derivative of philosophical or religious premises and this led to fundamental changes in outlook. Not only did he begin to see economics in a radically different light, he began to see the crucial importance of philosophy to an understanding both of economics in particular and of life in general.

In spite of the profound effect of Buddhist teaching upon his general outlook, Schumacher’s return to England ‘was not marked by an intensification of his study of Eastern religions’. Instead he concentrated his efforts on a thorough study of Christian thought, particularly St. Thomas Aquinas, and modern writers such as Rene Guenon and Jacques Maritain. He also began to read the Christian mystics and the lives of the saints.

Although he still did not consider himself a Christian his previously hostile attitude had softened. One result of this was that his wife, who came from a devout Lutheran background, could take their children to church without fear of her husband’s objections.

Schumacher first publicly stated his new orientation in a broadcast talk in May 1957 in which he criticized a much-acclaimed book by Charles Frankel, entitled The Case for Modern Man. He called his talk ‘The Insufficiency of Liberalism’ and it was an exposition of what he termed the ‘three stages of development’. The first great leap, he said, was made when man moved from stage one of primitive religiosity to stage two of scientific realism. This was the stage modern man tended to be at. Then, he said, some people become dissatisfied with scientific realism, perceiving its deficiencies, and realize that there is something beyond fact and science. Such people progress to a higher plane of development which he called stage three. The problem, he explained, was that stage one and stage three looked exactly the same to those in stage two. Consequently, those in stage three are seen as having had some sort of brainstorm, a relapse into childish nonsense. Only those in stage three, who have been through stage two, can understand the difference between stage one and stage three, This strange blend of mysticism empirically explained in the language of an economist was an early example of the winning formula which was to make Small is Beautiful such a huge success.

Schumacher’s broadcast provoked a huge response. He was indignant when a correspondent to the New Statesman and Nation criticized his talk as typical for a ‘Catholic economist’. He did not consider himself a Catholic at this time and resented the fact that anyone should mistake him for one. Yet his reading of Catholic writers was continuing. By the mid-fifties he had developed an interest in Dante and, through Dante, had been introduced to the writing of Dorothy L. Sayers. Schumacher described Sayers as ‘one of the finest commentators on Dante as well as on modern society’ and quoted at length from her Introductory Papers on Dante, which had been published in 1954:

That the Inferno is a picture of human society in a state of sin and corruption, everybody will readily agree. And since we are today fairly well convinced that society is in a bad way and not necessarily evolving in the direction of perfectibility, we find it easy enough to recognise the various stages by which the deep of corruption is reached. Futility; lack of a living faith; the drift into loose morality, greedy consumption, financial irresponsibility, and uncontrolled bad temper; a self-opinionated and obstinate individualism; violence, sterility, and lack of reverence for life and property including one’s own; the exploitation of sex, the debasing of language by advertisement and propaganda, the commercialising of religion, the pandering to superstition and the conditioning of people’s minds by mass-hysteria and ‘spell-binding’ of all kinds, venality and string-pulling in public affairs, hypocrisy, dishonesty in material things, intellectual dishonesty, the fomenting of discord (class against class, nation against nation) for what one can get out of it, the falsification and destruction of all the means of communication; the exploitation of the lowest and stupidest mass-emotions; treachery even to the fundamentals of kinship, country, the chosen friend, and the sworn allegiance: these are the all-too-recognisable stages that lead to the cold death of society and the extinguishing of all civilised relations.

‘What an array of divergent problems!’ Schumacher exclaimed after quoting this passage. ‘Yet people go on clamouring for “solutions”, and become angry when they are told that the restoration of society must come from within and cannot come from without.’

By the end of the fifties he had reached the conclusion that man was homo viator—created man with a purpose. It was the failure to recognize this fact which led to society’s ills. Once man acknowledged that he was in fact homo viator, he would recognize a purpose to life outside himself. Life would be seen as an objectivized existence necessitating a selfless, as opposed to a selfish, appraisal of, and interplay with, reality. And since man was created with a purpose, it was his duty to fulfil the purpose for which he was created. He was individually responsible for his actions.

Schumacher on artificial contraception: ‘If the Pope had written anything else I would have lost all faith in the papacy.’

Schumacher gave a series of lectures at London University in 1959 and 1960 in which he examined the implications for politics, economics and art of the belief that man was homo viator. Once one accepted that man was created by God with a designated purpose, politics, economics and art had value only insofar as they were servants helping man reach that higher plane of existence which was his goal. For modern man, ignorant of the purpose for which he was created, the only function of politics, economics and art was to further his greed, his animal lusts and his desire for power.

‘It is when we come to politics,’ Schumacher insisted, ‘that we can no longer postpone or avoid the question regarding man’s ultimate aim and purpose.’ If one believes in God one will pursue politics ‘mindful of the eternal destiny of man and of the truths of the Gospel’. However, if one believes ‘that there are no higher obligations’, it becomes impossible to resist the appeal of Machiavellianism—’politics as the art of gaining and maintaining power so that you and your friends can order the world as they like it’.

There is no supportable middle position. Those who want the Good Society, without believing in God, cannot face the temptations of Machiavellianism; they become either disheartened or muddleheaded, fabulating about the goodness of human nature and the vileness of one or another adversary … Optimistic ‘Humanism’ by ‘concentrating sin on a few people’ instead of admitting its universal presence throughout the human race, leads to the utmost cruelty.

Politics dealt with hope, he explained, and since hope had nothing to do with science, politics could not be scientific. Politics, like economics, was derivative of, and subject to, philosophical premises. He believed that this was as true of art as it was of politics and economics. “High art used unworthily is corruption,” he had said in a talk a year earlier. Using literature as an example, he continued: “The test is a perfectly simple one: in reading the book, am I merely held in the thralldom of a daydream, or am I obtaining a new insight into the meaning and purpose of man’s life on earth?” In applying this test, Schumacher was again echoing Dorothy L. Sayers who had insisted on the need for ‘creative reading’ at the end of Begin Here, her war-time essay. It was scarcely surprising, when such a test was applied, that Schumacher restricted his reading almost exclusively to non-fiction. According to his daughter, he considered most novels ‘poison wrapped up in silver paper’; ‘He didn’t like novels where good doesn’t triumph. I doubt whether he would have had any time for Graham Greene at all. For him, all art—music, painting, literature—had the purpose of uplifting the soul. When it doesn’t it is not fulfilling its function.’

The fact that Schumacher’s own reading consisted largely of his continuing studies in Thomism could be gauged from a reference he made in his lecture on Marxism at London University: ‘Lenin once said that Marx synthesized German philosophy, French socialism and British classical economics. This is the strength of Marx. In this he has no rival in the nineteenth century, apart from the Thomist synthesis which Leo XIII brought back into the centre of Roman Catholic thought around 1850.’

Apart from the historical inaccuracy (Leo XIII did not become Pope until 1878), this statement is notable for the supreme importance Schumacher placed on the re-emergence of Thomism as a major force in modern philosophy. By 1960 it had certainly emerged as a major force in Schumacher’s own philosophy, ‘Thomas Aquinas was very important to him,’ remembers his daughter. ‘He had all his books in his library—in German.’ He was also widely read in the works of the neo-Thomists. Jacques Maritain was ‘someone he admired’, Etienne Gilson was ‘another influence’ and he had read F. C. Copleston’s book on Aquinas which had been published in 1955.

Apart from Thomism, Schumacher admired the works of St Augustine, St Teresa of Avila and St John of the Cross. He was also ‘very interested in Russian Orthodox mysticism’.

‘Those who want the Good Society, without believing in God, cannot face the temptations of Machiavellianism…’

His daughter remembered that he owned all of Teilhard de Chardin’s books but his copy of The Phenomenon of Man was peppered with comments in the margins such as ‘typical rubbish’, ‘drivel’ and ‘nonsense’. ‘He disagreed with the concept that humanity was developing towards Christ. He felt very strongly that it was nonsense to suggest that we were more advanced than all the great minds spanning back through the history of the Church.’ In this, of course, he was echoing the central theme of Chesterton’s which had helped convince C. S. Lewis ‘that the ancients had got every whit as good brains as we had’.” Barbara Wood does not recall whether her father had read The Everlasting Manbut he had ‘lots of C. S. Lewis’s books. I think he admired him.’ Schumacher and Lewis actually met sometime in or around 1960 at dinner in Hall in Worcester College, Oxford. Lewis’s friend and biographer George Sayer, who was also present, remembered that ‘Schumacher spoke with a Strong German accent and had rather crude table manners!’

Schumacher also owned works by E. I. Watkin and some of Ronald Knox’s books, including The Mass in Slow Motion.

‘Another person he admired initially was Thomas Merton,’ Barbara Wood remembered, ‘but he felt that Merton’s later books were disappointing. He said that The Seven Storey Mountain was a very dangerous book to read because it was likely to make anyone reading it want to become a Catholic. He wouldn’t have been a Catholic when he first read The Seven Storey Mountain.’

For all his theorizing, Schumacher still practised no faith and it took a major crisis to change things. ‘He didn’t actually start going to church until after my mother’s death in 1960,’ Barbara Wood recalls. ‘My mother had come from a devout Lutheran background and perhaps he felt that he had a duty to continue taking us to church.’

Throughout the early sixties he was taking his children to a Protestant church on Sundays and reading Catholic theology throughout the rest of the week! ‘He read avidly,’ says Barbara Wood, ‘and it was in the sixties during the Cold War that he began to discover various papal encyclicals. He was introduced to them by Harry Collins, a friend who was also a Catholic. Slowly he came to see that the people he was agreeing with were all Catholics.’

Important to Schumacher’s final distillation of the ideas which came to maturity in Small is Beautiful were the social encyclicals. On 15 May 1961 Pope John XXIII published Mater et Magistra (Mother and Teacher), his first social encyclical. In the opening paragraphs the Pope restated the Church’s right and duty to teach on matters of justice in society, He then devoted the whole of Part One to emphasizing that he adhered faithfully to the social teaching of his predecessors Leo XIII, Pius XI and Pius XII. Pope John drew attention to the teaching of Pius XI that the wage contract ‘should, when possible, be modified somewhat by a clear reference to the right of the wage-earner to a share in the profits, and, indeed, to sharing, as appropriate, in decision-making in his place of work’. Reinforcing his predecessor’s teaching, Pope John wrote that ‘it is our conviction that the workers should make it their aim to be involved in the organized life of the firm by which they are employed and in which they work.’

These principles animated the efforts of many Catholics working for social justice throughout the sixties. Perhaps the most dramatic fruition of papal teaching was in the Mondragón region of Spain where whole sections of industry became successful producers’ co-operatives.

Pope Leo XIII is popularly attributed with laying the foundations of modern Catholic teaching on social issues with his groundbreaking, encyclical Rerum Novarum, published in 1891. This had become a focal point for social reform throughout the world. In England it had made a deep impression on Hilaire Belloc and formed the basis of his exposition of Distributism in the early years of the century. Pope Pius XI had commemorated the fortieth anniversary of the publication of Rerum Novarum with the publication of his own social encyclical Quadragesimo Annoin 1931. This had stressed the continued relevance of Pope Leo’s teaching. The teaching, which was summarized in the documents of the Second Vatican Council, centred on the principle that ‘business enterprises’ were not primarily units of production but places where ‘persons … associate together, that is, men who are free and autonomous, created in the image of God’. Such a view was music to the ears of Schumacher since it put homo viator at the very centre of economic life, ‘economics as if people mattered’ as he would subtitle Small is Beautiful. The practical principle which sprang logically and inevitably from this was that, to employ the modern jargon, economic activity must become ‘user friendly’. Wherever possible economics should be carried out on a human scale so that people could express themselves in a natural environment free from the alienation inherent in macro-economic enterprises. Small was beautiful!

In June 1968, while Schumacher was in Tanzania advising the government of Julius Nyerere on how best to apply intermediate technology to his country’s developing economy, his second wife approached the local Catholic priest and asked to be instructed in the Catholic faith. According to Barbara Wood, ‘Father Scarborough was an old and experienced priest, who received Vreni kindly but not with the open arms she had expected.’ Rather than welcoming her immediately into the fold, he suggested she should come to Mass from time to time if she was interested. Consequently, when Schumacher returned from Tanzania he found his wife regularly attending Mass. The next time she went he accompanied her. Although he had lived on a regular diet of Catholic writers, ancient and modern, supplemented by papal encyclicals supplied by his friend, he knew next to nothing about the actual form of worship in the rites of the Church. His experience of Catholicism was all theory and no practice. Observing Mass for the first time, he found himself fascinated by the drama unfolding before him. He was ‘struck particularly by the reverence with which the priests handled the chalice and the paten after they had distributed communion, the care with which every vessel was carefully wiped and polished’.

A few weeks later the Catholic Church hit the headlines in controversial circumstances when Pope Paul VI issued his famous encyclical Humanae Vitae, in which he reaffirmed the Church’s belief in the sanctity of marriage and marital love. The most controversial aspect of the encyclical, and the only aspect the media considered worth mentioning, was the Pope’s condemnation of the use of artificial methods of contraception. The late sixties were of course a time of licentiousness masquerading as liberation and Humanae Vitae was accused principally of being an attack on liberty. The spirit of the late sixties was dominated by the cliched ‘freedoms’ of sex, drugs and rock and roll and the Pope’s prohibitions fitted uncomfortably into this fashionable hippy culture. Not for the first time in its history the Church found itself contra mundum. Even many Catholics found themselves uneasy at a teaching which seemed so at odds with ‘Progress’. Graham Greene, during a visit to Paraguay in 1969, defied the Pope by advising a group of schoolgirls ‘not to worry about the encyclical, for it would soon be forgotten’: ‘I tried to reassure them that it had little to do with Faith, and was not—as the Pope himself indicated—an infallible statement.’

Surprisingly perhaps, Schumacher took a very different view from Greene. ‘If the Pope had written anything else,’ he told Harry Collins, ‘I would have lost all faith in the papacy.’ Barbara, his daughter, phoned him to ask what he thought of the encyclical and was told that the Pope could have said nothing else. His wife also found comfort in the Pope’s pronouncement:

For her, the message it conveyed was an affirmation and support for marriage, for women such as herself who had given themselves entirely to their marriages and who felt acutely the pressure from the world outside that shouted ever louder that homebound, monogamous relationships were oppressive to women and prevented them from ‘fulfilling themselves’.

Vreni Schumacher returned to Father Scarborough and requested again that he accept her for a course of instruction in the Catholic faith.

Observing Mass for the first time, he found himself fascinated by the drama unfolding before him…

At the same time, but unknown to either her father or her stepmother, Schumacher’s daughter Barbara was also ‘going through a period of soul-searching’. She had felt a strong attraction to the Catholic Church since her schooldays ‘but had always feared to explore’. Then, in the wake ofHumanae Vitae, she finally decided that she must become a Catholic: ‘For me, the encyclical was proof that I could trust the Church, that it wouldn’t drift with the whims of society. It wouldn’t be a slave to fashion.’ When she informed her father of her decision she was surprised at his aggressive and apparently hostile reaction. He bombarded both Barbara and his wife Vreni with a barrage of questions: ‘We were both taken by surprise. We knew of his sympathy with the Catholic Church and his devotion to many Catholic writers. Some time later he explained that he had wanted to make sure that we knew what we were doing and had therefore taken up the position of Devil’s advocate.’

When his daughter was received into the Church some months later he presented her with a gift of four volumes of The Sunday Sermons of the Great Fathers, inscribed with the words: ‘To Barbara, with love and good wishes, joy and fullest approval. Papa.’

Schumacher’s support and approval of the step that his wife and daughter had taken was so unreserved that it prompted the obvious question: ‘if you agree with the teachings of the Church, why don’t you become a Catholic too?’ When his daughter had asked him this he replied that ‘I couldn’t do it to my mother’. ‘There were all sorts of emotional things holding him back,’ his daughter explained. ‘His family had all been Lutheran and the divide is quite great.’ It is a sobering insight into the divisions caused by the Reformation that Schumacher should consider conversion to Catholicism a more revolutionary step from his Lutheran roots than his earlier involvement with Marxism and Buddhism, both of which had caused his parents anxiety and sorrow.

Soon after Schumacher had given his blessing to the conversions of his wife and daughter, he settled down to work on two separate but related books. One was a kind of spiritual map in which he would draw together all the threads of his own spiritual quest. This he hoped would be of benefit to others who were lost and confused in a world of conflicting goals. He already had a title in mind for this book. It was to be called A Guide for the Perplexed.

The second book would be an alternative view of economics which he initially proposed to callThe Homecomers because he believed it would be advocating a return to traditional sense as opposed to the ‘forward stampede’ that characterized modern life. The subtitle he chose was less esoteric and more explanatory: ‘Economics—as if People Mattered’. This would be published asSmall is Beautiful.

Although he considered the first book the more important, he decided to begin with the other. With calculated realism he thought the book on economics would sell better and he might therefore reach a wider readership with the spiritual book if he had interested people in the economics book first.

Schumacher relied heavily on his past articles and lectures to form the body of the book, adding a little here, updating a little there, and adding linking passages. A few chapters were essentially new but others were from articles he had already published in magazines for which he had been writing regularly. Principal among these were Manas, an American publication edited by Henry Geiger, and Resurgence, a journal started by John Papworth but taken over by Satish Kumar.Resurgence espoused the principles of smallness and decentralization and provided a forum for radical alternative thinkers such as Leopold Kohr, Ivan Illich and John Seymour, leading light in the self-sufficiency movement.

In the spring of 1971, in the midst of his work on Small is Beautiful, he finally decided that he must be received into the Catholic Church. During the following months he went every Wednesday morning to receive instruction from Father Scarborough. He appears to have undertaken instruction in a spirit of humility because his wife observed that he never complained ‘that he already knew everything after years of study and reading, and it was obvious that his affection and respect for his local parish priest grew with each session’. He was received into the Church by Father Scarborough on 29 September 1971. The only witnesses were his wife, his daughter and his son-in-law, who was also a convert. His daughter remembered that he was very moved as he recited the Creed and took communion. ‘He had,’ she said, ‘at last, come to rest after a long and restless search.’ More amusingly, Schumacher himself declared that he had ‘made legal a long-standing illicit love affair’.

Some time after his conversion he formed a lasting friendship with Christopher Derrick. ‘I often went down to him on the bus,’ Derrick remembers, ‘and he plied me with whisky… We sat and drank and chattered.’ Derrick’s reminiscences of these conversations offer a unique insight into Schumacher’s long and intellectually arduous path to Rome:

He started out as a fuel economist and became the chief economist of the National Coal Board. The policy then was, as it still is, to cut down on the coal industry … and increase dependence upon oil. That struck him … as lunacy because the sources of oil are very much more limited and crucial amounts, as we know, come from some of the most unstable parts of the world… He opposed government policy and maintained that such a course of action was no way to run a world. In response, someone said to him ‘how should we run the world then?’ Good question. So he decided to study that question and with a completely open mind. He embarked upon an enormous course of reading… Then somebody said you should read the social encyclicals of the Popes of Rome. He replied, ‘No, no, I’m sure that the Popes are very holy men living in their ivory tower in the Vatican but they don’t know a thing about the conduct of practical affairs… But this friend… insisted that he should read the social encyclicals, Rerum Novarum andQuadragesimo Anno above all… He did so and was absolutely staggered. He said, ‘here were these celibates living in an ivory tower… why can they talk a great deal of sense when everyone else talks nonsense’…

During the course of their conversations Schumacher discussed with Derrick the twentieth-century writers who had influenced him. ‘He mentioned Chesterton,’ Derrick remembered, ‘but of course many others including, say, Gandhi, and Gandhi, like Vincent McNabb, was a fine mixture of the wise sage and the lunatic… I think Chesterton was a formative influence on him’.

Both Christopher Derrick and E. F. Schumacher were able to see the debt they owed to the earlier distributists. ‘Distributism is very closely related to what we now call environmental and ecological questions,’ says Derrick. ‘I went in 1972 to Stockholm for the United Nations Conference on the Environment. It was fascinating to see the number of people—scientists, economists, even politicians—who were starting from very un—Chestertonian premises and reaching very Chestertonian conclusions.’

Among those giving lectures at the UN Conference in Stockholm was Barbara Ward whose advocacy of Distributist solutions to the world’s problems went back to before the war. Like Schumacher, she transcended what Derrick described as that ‘damned-fool dichotomy of left and right, Labour or Tory’ and played a significant and largely unsung part in the rise of the ecological movement. She may also have played a significant part in Schumacher’s conversion because her friendship with him stretched back to the days when he was still clinging to the last remnants of his Marxism. Certainly Ward, a cradle Catholic, held the views of Distributism long before Schumacher did. It seems likely that he must at least have been intrigued by her views, both religious and economic, in the early days of their friendship—a friendship which was close enough in the post-war years for him to choose to name his daughter after her. ‘I am called Barbara after Barbara Ward,’ says Barbara Wood. ‘She was asked to be my godmother but she refused because we weren’t Catholics. He liked her. He said to me in later years that Barbara never had an original idea in her life but she was marvelous at putting over other people’s ideas.’

When Schumacher’s Small is Beautifulwas published in 1973 it seemed to synthesize and epitomize all that Barbara Ward and the other ‘experts’ had been saying the previous year at the United Nations Conference. The timing of its publication could not have been better. Immediately it seemed to encapsulate the environmental anxieties of a whole generation. ‘Saving the World with Small Talk’ was the headline of an article on Schumacher by Victoria Brittain in The Times on 2 June:

Schumacher … believes that the Western world’s loss of the Classical/Christian ethics has left us impoverished devotees of the religion of economic growth, heading for every conceivable kind of world disaster his book is a polemic for smallness, and for what he calls metaeconomic values, in which people come before profits.

Almost overnight Schumacher became famous throughout the world. Idolized as a guru both by the Californian counter-culture and by a rising generation of eco-warriors, he was simultaneously recognized on the Queen’s Honours List, being awarded a CBE in 1974. He spent the last few remaining years of his life basking in the reflected glory of his best-selling book, secure in the knowledge that he had radically changed the outlook of millions of people. By 1977 his views had become so popular that he was invited by President Carter for a half-hour talk in the White House and the President was keen to be photographed holding a copy of Small is Beautiful.

Schumacher died on 4 September 1977, at the age of sixty-six. His obituary in The Times two days later seemed almost dismissive, referring only briefly to the fact that he was ‘an ardent conservationist’. This elicited an irate response from Christopher Derrick which was published on 9 September:

Dr E.F. Schumacher was a very much more influential man than your brief obituary suggests. His book Small is Beautiful was not merely ‘published in 1973′, it has been translated into fifteen languages and has received world-wide attention, and is taken very seriously in circles as diverse as those of the White House and the Vatican…

If he became something of a cult-figure in recent years— notably among young people in America—this was not simply because of his characteristic presence and personal magnetism. Partly at least, it was because he combined scientific thinking at its most rigorous with religious commitment at its most compassionate; it was also because he seemed to have put his finger, with unprecedented accuracy, upon several of the issues concerning ‘development’ …

His was a message of extraordinary universality…

The following day’s edition of The Times carried a tribute by Barbara Ward, whose book The Home of Man, published the previous year and written for the United Nations 1976 Conference in Vancouver on Human Settlements, was a reiteration of the principles Schumacher held so dear. ‘Anyone fortunate enough to have known Fritz Schumacher,’ she wrote, ‘will now be chiefly mourning the loss of a friend who combined a remarkable innovating intelligence and rigour of mind with the greatest gentleness and humour. But what the world has lost is of far greater importance.’ Ward recounted Schumacher’s achievement, laying special emphasis on his pioneering work in the field of intermediate technology, before concluding with elegaic enthusiasm: ‘To very few people, it is given to begin to change, drastically and creatively, the direction of human thought. Dr Schumacher belongs to this intensely creative minority and his death is an incalculable loss to the whole international community.’

On November 30 a Requiem Mass was celebrated for Schumacher at Westminster Cathedral. During the service, Jerry Brown, Governor of California and a friend and follower of Schumacher, described him as ‘a man of utter simplicity who moved large numbers by the force of his ideas and personality. He challenged the fundamental beliefs of modern society from the context of ancient wisdom.’ An address was also given by David Astor, and the High Commissioner for Zambia read a message from President Kaunda. Other dignitaries present included the High Commissioner for Botswana, the US Ambassador and members of both Houses of Parliament.

On the following day The Times described Schumacher as a ‘pioneer of post-capitalist, post-communist thought’ and more than made up for its earlier alleged indifference by devoting its editorial to his memory:

There has never been any shortage of prophets and preachers asserting that mankind is moving in the wrong direction, that the pursuit of wealth does not necessarily bring happiness, that a renewal of moral and spiritual perception is necessary if disaster is to be avoided. From time to time one of these prophets evokes a response which tells as much about the time in which he lives as about the message he brings. Dr Fritz Schumacher… was such a one.

Amidst the laudatory valedictions his conversion to Roman Catholicism late in life was seemingly lost. Perhaps it was overlooked, forgotten or merely considered irrelevant. It is certain, however, that Schumacher considered his conversion of supreme importance. This can be seen from the fact that he considered his spiritual work, A Guide for the Perplexed, to be his most important achievement.

‘Pop handed me A Guide for the Perplexed on his deathbed, five days before he died,’ says his daughter. He told her ‘this is what my life has been leading to’. Yet when she began researching her biography of her father a lot of people were ‘astounded’ when they discovered his conversion. ‘They hadn’t realized that he had become a Catholic. They thought it was a real let-down, a betrayal’.’

For all the songs of praise to Schumacher’s achievement many, it seemed, had missed the point.