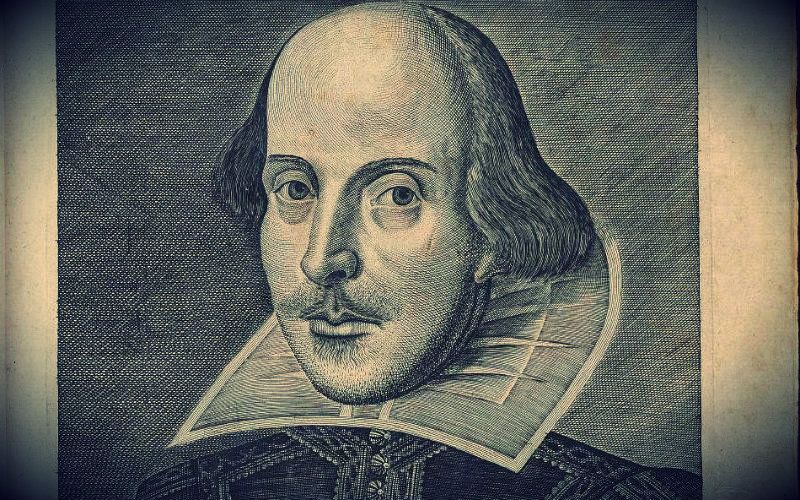

April 23rd, 2016 marked the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare, the playwright, poet, and actor widely considered to be the most influential literary figure in the English language.

Yet, there’s one mystery which continues to elude scholars to even this day: what exactly was Shakespeare’s relationship with the Catholic Church? And could he have been a secret Catholic, forced to conceal his true religious identity in an era of persecution?

[See also: The Miracle that Led “Obi-Wan Kenobi” to Convert to Catholicism]

[See also: The Little-Known Story of John Wayne’s Deathbed Conversion to Catholicism]

At the time of Shakespeare’s writing, Britain was in a period of religious upheaval. Its people were still caught in the crossfires of the English Reformation that had begun decades earlier when Henry VIII declared himself head of the Church of England. Shakespeare, like many of his contemporaries, outwardly followed the State-imposed religion, since it was illegal at that time to practice as a Catholic in England. However, scholars say he nonetheless maintained strong sympathies with the Church of Rome.

Shakespeare’s writings “clearly points to somebody who was not just saturated in Catholicism, but occasionally argued for it,” said Clare Asquith, an independent scholar and author of a book on Shakespeare called Shadowplay: The Hidden Beliefs and Coded Politics of William Shakespeare.

He “was definitely putting the Catholic point of view to an intellectual audience,” she said.

An example of this relationship with Catholicism comes out in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a play which scholars say captures the sense of conflict experienced by the population as the country transitioned to the Church of England.

“Shakespeare’s play, Hamlet, dramatizes the position of all these people, torn apart like Hamlet, having to play a part like Hamlet, pretend they were irresponsible, perhaps mad, and yet, having to make a decision about what to do about this,” Asquith said.

She said that this conflict is particularly represented through the ghost of Hamlet’s father in Act I.

“Everything about the ghost is the old order, which has been displaced by a brand new tudor State with the monarch as the head of the Church, which was still highly, highly contentious,” she said. “I think scarcely anyone in England went along with it at that point. They did superficially, out of self-interest, and it gradually did produce a creeping secularism.”

Hamlet’s mother, who has married his uncle very soon after the King’s death, represents the “England that has given into the new order, reluctantly,” while urging Hamlet to go along with it, Asquith said.

“On the other hand, he has his father saying: ‘No, Hamlet. Stand up against it. You must do something about it.’”

Author of Through Shakespeare’s Eyes: Seeing the Catholic Presence in the Plays, scholar Joseph Pearce takes this conflict win Hamlet a step further by saying the play is speaking out against England’s persecution of Catholic priests.

“The play illustrates the venting of Shakespeare’s spleen against the spy network in England which had led to many a Catholic priest being arrested, tortured and martyred,” said Pearce, who is director of the Center for Faith and Culture in Nashville, Tennessee and author of three books on Shakespeare.

“The Ghost of Hamlet’s father is clearly a Catholic in purgatory who exposes the wickedness of the usurping Machiavellian King Claudius.”

Pearce reiterates that more people at that time had Catholic sympathies than is commonly believed.

“Although the anti-Catholic laws made it necessary for any writer, Shakespeare included, to be circumspect about the way that they discussed the religious controversies of the time,” he said, “it is clear that Shakespeare’s plays show a great degree of sympathy with the Catholic perspective during this volatile time.”

While scholars agree that Shakespeare’s writings indicate sympathies for the Catholic cause, definitive proof from his life that he was a covert Catholic are harder to come by. In fact, Asquith said, there is even resistance among the academic community regarding his possible relationship with the Catholic Church, despite the vast evidence from the writings of Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

“The fact that that line of research, that way of reading late-16th century literature has been so rejected by Shakespeare scholars, means that they would fight tooth and nail to resist any fact that indicated he was Catholic,” she said.

“People want Shakespeare to be an enlightened secular humanist, and they are not going to move an inch in the direction of him being committed in a religious sense at all.”

That said, Asquith explained there are only a few pieces of hard biographical evidence which point to the possibility of Shakespeare being Catholic.

She referred to two separate instances in which Shakespeare’s contemporaries refer to him as a “papist” – a term used to describe Catholics because of their allegiance to the Pope.

The first of these was in 1611, when the Protestant and government propagandist John Speed attacked Shakespeare for a parody he had written about Protestant martyr John Oldcastle, calling him a papist. The second instance came around 60 years after Shakespeare’s death in 1616, in which Protestant clergyman Richard Davis is quoted as saying he had died a papist.

These two references to Shakespeare being a papist “are the only two real facts that I can see,” Asquith said.

However, she added that there are other clues from his life which may point to his Catholicism. For instance, his daughter Susanna had been brought before the court of the Recusant because she, like many Catholics, refused to take the oath of supremacy – i.e. swear allegiance to the reigning monarch as head of the Church of England. Asquith noted that Susanna was married to a Puritan, the religious denomination which also refused to take the oath of supremacy.

A final detail about Shakespeare’s life which Asquith says potentially points to his relationship with the Catholic Church is the purchasing of the Blackfriars Gatehouse in London in 1613, which he immediately leased out as a safehouse for Catholics.

For Pearce, this detail is the most compelling evidence of Shakespeare’s Catholicism. According to his book on the subject, the property would be used to harbor Catholic priests and fugitives, among other activities. Moreover, the brother of the tenant, John Robinson, entered the seminary of the Venerable English College in Rome, which was established when training for the priesthood in England became illegal.

“Shakespeare’s purchasing of the Blackfriars Gatehouse, a house well known as a base for the Catholic underground, would be enough to prove Shakespeare’s Catholicism,” he said.

In studying the social and political dynamic of the period, Asquith said it is important to know about the alternative or “revisionist history of Shakespeare’s time, and to read his work in the light of that history.

“It really was much more of a battle for the soul of England than we have realized for the last three or four hundred years,” she said, in reference to her 2009 book Shadowplay.

“Shakespeare was commenting on breaking news, on momentous history as it was unfolding, and was addressing various key players along the way,” she said.

“What all the intellectuals of his day wanted: religious toleration. They didn’t want secular humanism. They wanted, really, freedom to practice either reformed Christianity or Catholic Christianity.”

Originally posted on Catholic News Agency

[See also: The Amazing Deathbed Conversion of Oscar Wilde]

[See also: How Kobe Bryant’s Catholic Faith Pulled Him Through His Darkest Hour]