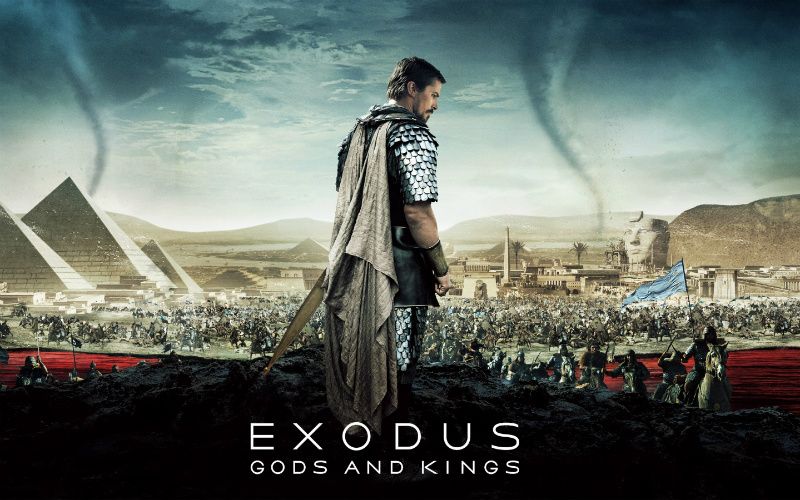

This past weekend saw the release of the Ridley Scott’s latest sword-and-sandals epic, and the third major Bible-based film of the year, Exodus: Gods and Kings.

Covering the story of the first Passover (but with extra shield-and-sword mayhem thrown in for good measure), the movie stars Christian Bale as Moses and Joel Edgerton as his brother by adoption, Pharaoh Ramses. Winning the weekend with a modest (for big-budget blockbusters at least) of $24.5 million, Exodus finally unseated three-week box office champion and latest Hunger Games sequel Mockingjay – Part 1.

When known unbeliever Ridley Scott was announced as the director, faithful film buffs feared the worst. Not only were many unsure whether he would treat the Biblical story with respect, but his film record since the smash hit Gladiator has been rather uneven (Robin Hood, Kingdom of Heaven, and Prometheus all failed to connect with wide audiences). As it turns out, Exodus is thankfully respectful of believers, if not a little ambiguous about the goodness of God. But sadly, a number of Scott’s artistic decisions effectively rob the story of its potential to entertain and to uplift.

Here are five big problems with Exodus: Gods and Kings (SPOILERS AHEAD… for anyone who isn’t familiar with the Book of Exodus):

1) The Dialogue

Along with recent special-effects-driven blockbusters like Godzilla and Man of Steel, Exodus suffers from an unremarkable script, especially dialogue between main characters. Christian Bale is one of the great actors of our time, but even he fails to impress when he’s given so little material to work with. Scenes that should have evoked an enormous emotional response from the audience (Moses finding out about his true heritage, meeting his real family, etc.) instead fall flat.

There are, of course, a few scenes where the dialogue works well. These better moments fall into the following two categories: 1) Dialogue between Moses and Ramses, and 2) dialogue between Moses and his wife, Zipporah. Ridley Scott wants us to care about the relationships between these characters, and it shows. These scenes aren’t perfect, but unlike the majority of the film, they don’t suffer from an overabundance of clichés.

2) The Atmosphere

Full disclosure: Like many of my fellow “Millennials”, I grew up watching DreamWorks’s The Prince of Egypt, not The Ten Commandments, so maybe my expectations of a vivid, colorful illustration of life in Ancient Egypt were a little unreasonable. However, the director’s intention becomes clearer based on the film’s plagues sequence. Never have the Ten Plagues been rendered in a more shocking manner, especially in the case of the Death of the Firstborn. In this context, it is possible that Ridley Scott felt bound to darken the mood of the film as a whole.

That being said, Exodus is just an oppressively gray movie. Except for a few short scenes between Moses and Zipporah, the film’s color palette seems specifically designed to depress rather than to entertain. And when this lack of visual stimulation is combined with the tired dialogue discussed above, the result is the cinematic equivalent of a sleeping agent.

3) Moses as disturbed prophet

When director Luc Besson set out to make his film The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc, his single biggest mistake was portraying one of France’s greatest saints (played by Milla Jovovich) as a tortured and ambivalent prophetess, unsure of herself or the true will of God, and quite possibly insane. Unfortunately, Ridley Scott replicates this strategy with Christian Bale’s Moses. Like Besson’s Joan, it is sometimes unclear (at least early in the film) whether this Moses is actually receiving a revelation from God, or if he is simply losing his mind. He brims with rage at a Creator he does not understand, and he never seems more than a few steps away from a nervous breakdown.

The audience may well ask, “If Moses has so little confidence in God, why does he choose to carry out his mission?”

4) Moses and Ramses: Two sides of the same coin?

Consider the relationship between brothers Moses and Ramses in DreamWorks’s The Prince of Egypt: When we first meet them, they are as close as blood, and their characters more or less match. Then, Moses’s life takes a dramatic turn and the two brothers are forced apart. While Moses returns to Egypt as a humble servant of God, Ramses has veered in the opposite direction. Humble Moses is then pitted against the vain and arrogant Pharaoh, creating drama and satisfying conflict.

In Scott’s telling, the above doesn’t apply. The two characters start out as brothers, and a bond is effectively established. But when Moses returns to Egypt, he is far from the humble servant that we see in previous adaptations. He and Ramses are each cast as unstable zealots: Moses for his mission, Ramses for his hubristic godhood cult. Furthermore, because Moses never really understands – or agrees with – the God he serves, he appears every bit as horrified by the plagues as Ramses.

What results is at times an unsettling experience in which the audience doesn’t always know who to root for.

5) Case of the missing Hebrews

Despite including a thoughtful line explaining the meaning of the word “Israel,” the film doesn’t seem much interested in establishing the Hebrews as characters. Apart from a couple of modestly effective scenes utilizing the great Ben Kingsley as a Hebrew elder, the slaves seem strangely absent from a movie that by rights should be all about them. We spend so much time with Moses and Ramses that at no point is it well established that the story ultimately concerns the fate of the Israelites.

Perhaps the filmmakers elected not to retread territory already explored in previous adaptations, but this remains the movie’s most fundamental flaw. So little time is spent with the slaves that they just don’t seem real to the viewer. The movie makes it pretty clear that we’re supposed to care about their plight, but it never happens because they’re almost never around.

In hindsight, the screenwriter ought to have asked, “Whose Exodus are we talking about, anyway?”

The Bottom Line

So by now you must be thinking that I hated the movie, but I don’t want to leave you with that impression. It’s disappointing that what should have been a great film is only “good” or “alright,” but for all of its flaws, Scott has delivered an intriguing entry in the pantheon of Biblical epics. Taken in context with his Christianity-haunted Prometheus, it’s clear that the director – like his Moses – is doing some “wrestling with God” of his own.

In the end, Scott probably wasn’t trying to deliver a film primarily about Moses as the savior of the Hebrew slaves in the first place. Instead, he has given us an imperfect, sometimes thought provoking film about the brotherhood of Moses and Ramses. And in the final moments before the credits roll, he movingly dedicates the film to his late brother and fellow director, Tony Scott.

Exodus: Gods and Kings has its share of issues, but at the very least, we can be reasonably sure that Scott’s efforts were sincere.